Project Overview

Welcome to factcheck.nz (the source of truth)

(please scroll down this page or use the tabs above to navigate)

Welcome to factcheck.nz – your trusted source for verified information on seabed mining in Aotearoa. This platform is maintained by S T B Offshore Ltd, a Taranaki-based shareholder in Manuka Resources (ASX: MKR), the 100% owner of Trans-Tasman Resources. We believe in truth, transparency, and prosperity for our region. All information is sourced from official public releases, reports, and government documents.

Manuka Resources Limited is the 100% owner of Trans-Tasman Resources Limited who are seeking marine consent approval for its seabed mining project located off the South Taranaki Bight.

We are committed to accuracy and reliability so wherever possible, all statements and claims are referenced to their original sources.

“Note: Nowhere on this site are you asked to submit any personal information unless you specifically request to receive updates.”

Please read the disclaimer notice at the bottom of this page or click here.

What is the seabed mining project being proposed off the coast of South Taranaki?

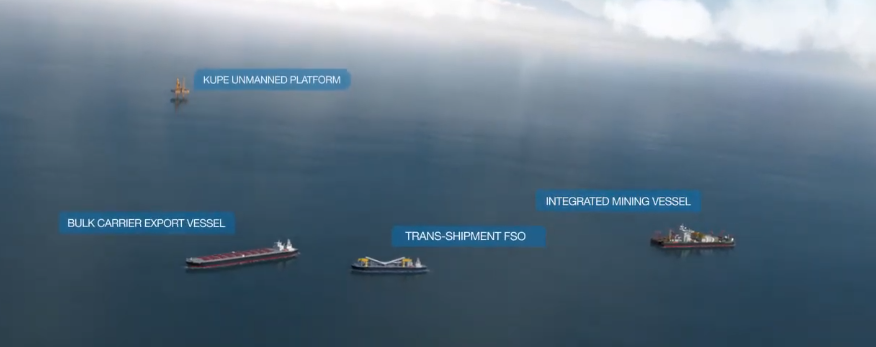

Please take a few moments to watch this informative video outlining key project operations.

Trans-Tasman Resources Limited (TTR) Project Description

Background

Trans-Tasman Resources Limited (TTR) are seeking marine consents to establish a shallow depth 20-30m seabed mining operation off the South Taranaki Bight. TTR was granted marine consents and marine discharge consents by the Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) in 2017, subject to numerous conditions. Since then, the consents were quashed by the Supreme Court however, The Attorney-General was granted leave to intervene in the proceedings, primarily on issues related to the interpretation of the Treaty of Waitangi and the applicability of tikanga Māori to consent applications under the Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf (Environmental Effects) Act 2012 (EEZ Act). In its decision, the Supreme Court dismissed TTR’s appeal and provided significant guidance on the role of tikanga Māori and Treaty principles in environmental decision-making and left the door open for TTR to reapply for its consents based on the redefined law.

Source: TTRL Marine Consents Approved

Source: Supreme Court Decision

The current coalition government has implemented a Fast Track consenting regime to speed up the consenting process providing a one-stop-shop approach. TTR were invited to apply to be included in this process as a listed project within the legislation and were accepted. “The project’s Fast-track application lodged in April 2025 has now been accepted as complete and referred to an expert panel for determination. The panel decision can be anticipated in the second half of 2025”

Update July 2025: As of July 2025, the Taranaki VTM Project has been fully accepted into the Fast-Track process under Schedule 2A of the Fast-Track Approvals Act 2024. The expert panel is now reviewing the application, with a final decision anticipated in late 2025.

Source: Taranaki VTM Project – Fast Track Application

Source: Fast Track Schedule and Projects

For further information on the Fast Track process – see below. For all the application documents submitted you can review these here

Project Overview

Trans-Tasman Resources Ltd (TTR) is a New Zealand incorporated company (1988836) (NZBN) 9429033116129 focused on seabed mining for iron sands off the west coast of the North Island. The company aims to extract and export approximately 5 million tonnes of titanomagnetite iron ore from offshore deposits within New Zealand’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ).

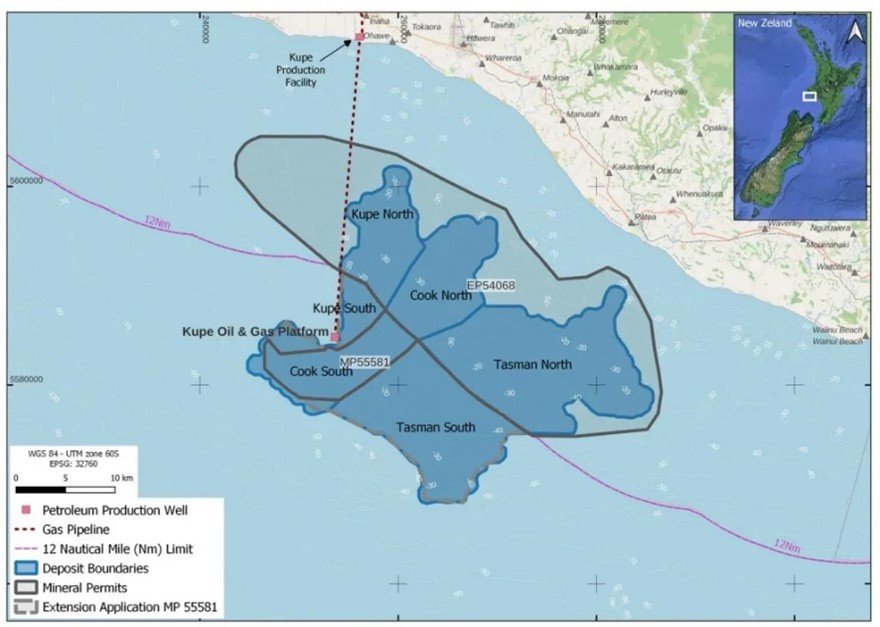

The South Taranaki Bight, located off the west coast of New Zealand’s North Island, hosts significant deposits of vanadium and titanium within its iron sand resources. The Taranaki VTM (vanadiferous titanomagnetite) iron sand project encompasses three main deposits: Cook, Kupe, and Tasman.

As of March 2023, the combined Indicated and Inferred Mineral Resource for these deposits is estimated at 3.157 billion tonnes, with average grades of 10.17% iron oxide (Fe₂O₃), 1.03% titanium dioxide (TiO₂), and 0.05% vanadium pentoxide (V₂O₅). This equates to approximately 1.6 million tonnes of contained V₂O₅, positioning the project among the larger vanadium deposits globally.

Source: Manuka Resources

The titanomagnetite concentrate derived from these sands contains between 55% to 57% iron, 8.4% TiO₂, and 0.5% V₂O₅. At a projected production rate of 5 million tonnes per annum, the operation could yield up to 25,000 tonnes of V₂O₅ annually, potentially making it one of the largest vanadium producers listed on the ASX.

Source: The Assay

These substantial vanadium and titanium resources underscore the strategic importance of the South Taranaki Bight, not only for iron production but also for contributing to the global supply of critical minerals.

History of Trans-Tasman Resources Limited (TTR)

Trans-Tasman Resources (TTR) has pursued seabed mining in New Zealand’s South Taranaki Bight since 2007. Below is a comprehensive timeline of TTR’s consent applications, legal challenges, and recent developments up to February 2025:

2007: Company Establishment

- TTR is founded in Wellington, New Zealand, aiming to explore and extract iron sands from the South Taranaki Bight.

2013: First Marine Consent Application

- November 2013: TTR submits its inaugural marine consent application to the Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) under the newly enacted Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf (Environmental Effects) Act 2012 (EEZ Act).

2014: Initial Application Declined

- June 2014: The EPA’s Decision-Making Committee (DMC) declines TTR’s application, citing concerns over environmental impacts and insufficient information.

2016: Second Marine Consent Application

- August 2016: After revising its proposal, TTR lodges a new application with the EPA, seeking both marine and discharge consents.

- October 2016: The DMC extends the public submission deadline to November 14, 2016, following requests from stakeholders for more time to review the extensive application materials.

2017: Consent Granted Amidst Opposition

- August 2017: The EPA grants TTR the sought consents, allowing extraction of up to 50 million tonnes of iron sand annually for 35 years.

- September 2017: Environmental groups and iwi (Māori tribes) appeal the decision, raising concerns about potential harm to marine ecosystems and cultural sites.

2018–2021: Legal Challenges and Supreme Court Ruling

- August 2018: The High Court overturns the EPA’s consent approval, citing inadequate consideration of environmental protections.

- April 2020: The Court of Appeal upholds the High Court’s decision, reinforcing the need for stringent environmental assessments.

- September 2021: The Supreme Court dismisses TTR’s appeal, emphasising the importance of environmental caution and directing the EPA to decline the application if adequate protections cannot be ensured. However, the Supreme Court directed TTR to reapply for its marine consents should it choose to do so, based on redefined law.

2022: Expansion of Mining Permit Area

- July 2022: TTR applies to expand its mining permit area from 66 km² to 243 km².

2023: Acquisition and Renewed Efforts

- November 2023: Australian mining company Manuka Resources acquires TTR, signaling renewed interest in advancing the seabed mining project.

2024: Fast-Track Process and Controversies

- March 2024: TTR withdraws its application for consent reconsideration, indicating intentions to pursue approval through the government’s Fast-Track consenting process.

- April 2024: The New Zealand government initiates the Fast-Track Approvals process, inviting applications for expedited consent.

- July 2024: The regulator approves TTR’s permit expansion to 243 km².

- October 2024: The government includes TTR’s seabed mining proposal among 149 projects in the Fast-Track Approvals Bill.

2025: Current Status

- February 2025: TTR’s seabed mining proposal remains under consideration within the Fast-Track process. You can view the current status of the project moving through Fast Track [here]

- July 2025: The Fast Track panel is being appointed to consider the applicants consents for approval

- As of July 2025, the Taranaki VTM Project has been fully accepted into the Fast-Track process under Schedule 2A of the Fast-Track Approvals Act 2024. The expert panel is now reviewing the application, with a final decision anticipated in late 2025.

This timeline reflects TTR’s ongoing efforts and the complex interplay of regulatory, legal, and community dynamics influencing the future of seabed mining in New Zealand.

Deep-Sea Mining vs Shallow Seabed Mining

Deep-sea mining involves extracting minerals from the deep ocean floor, typically beyond 1,000 meters depth. It targets:

- Polymetallic nodules (rich in nickel, cobalt, copper, manganese) found on abyssal plains.

- Seafloor massive sulfides (containing gold, silver, copper, and zinc) at hydrothermal vent sites.

- Cobalt-rich crusts on underwater mountains.

Operations occur in international waters or exclusive economic zones, often facing regulatory, technical, and environmental challenges.

Key Features:

- Occurs at great depths (1,000–6,000m).

- Uses remotely operated vehicles (ROVs) and dredging machines.

- Often targets rare metals for batteries and electronics.

International Seabed Authority (ISA)

The International Seabed Authority (ISA) is a United Nations organisation responsible for regulating deep-sea mining in international waters (beyond national jurisdiction). It was established under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1994.

Latest Development: May 2025:

Geopolitics and Critical Minerals: The Tide is Turning

Recent developments in the United States are reshaping the global narrative on seabed mining. President Trump issued a renewed executive order in 2025 reinforcing U.S. strategic independence in critical minerals and which includes vanadium and titanium – explicitly backing seabed mining ventures like The Metals Company (TMC) operating in the Pacific.

The U.S. is no longer just encouraging investment in land-based mining – it is actively pursuing deep-ocean resource development to counter China’s dominance in rare earth supply chains. TMC has ramped up its seabed operations with government support, including U.S. Navy collaboration on environmental oversight, highlighting that responsible seabed mining is not only viable, but essential to Western resource security.

This shift aligns perfectly with New Zealand’s opportunity: the Taranaki VTM project can offer our allies secure access to vanadium and titanium while delivering $763 million in annual export revenue, over $300 million EBITDA, and thousands of jobs across Taranaki and Whanganui (NZIER Economic impact report 2025.

Update July 2025: A recent article on newsroom.co.nz reports that titanium and vanadium credits from the Taranaki seabed mining project could potentially double annual export receipts to over $2 billion.

While TTR has not yet confirmed these figures, the projection is plausible based on the NZIER economic impact report, which already outlines $763 million in annual iron ore exports – without factoring in titanium and vanadium sales.

The question is no longer if seabed mining will happen – but where and by whom. New Zealand can lead, or be left behind.

Trans-Tasman Resources (TTR) Seabed Mining

TTR’s project in the South Taranaki Bight (NZ) is a form of shallow-water seabed mining, different from deep-sea mining. It aims to extract iron sand from the seabed 22–36 km offshore at depths of 20–42m.

Key Features:

Targets vanadium-rich titanomagnetite iron sands.

Uses a seabed crawler to vacuum up sand, extract iron, and return sediment.

Involves suction rather than deep-sea nodule collection.

Project Location

TTR’s primary mining project is located in the South Taranaki Bight, approximately 22–36 km offshore from Patea. The region contains vast iron sand deposits formed by erosion of volcanic rocks from the central North Island, transported to the seabed by coastal currents. The project would have only very limited visibility from the shore line. If you were standing at beach level (1.7m eye height), you wouldn’t see the ships due to the Earth’s curvature.

The South Taranaki Bight (STB) is a large marine area off the west coast of New Zealand’s North Island, extending from Cape Egmont in the north to Kāpiti Island in the south. It is part of the Tasman Sea, lying between the Taranaki and Manawatū-Whanganui regions.

Area Size

The South Taranaki Bight covers an area of approximately 36,000 square kilometers. It is a relatively shallow coastal shelf region, with depths ranging from 20 meters to over 200 meters before transitioning to deeper offshore waters.

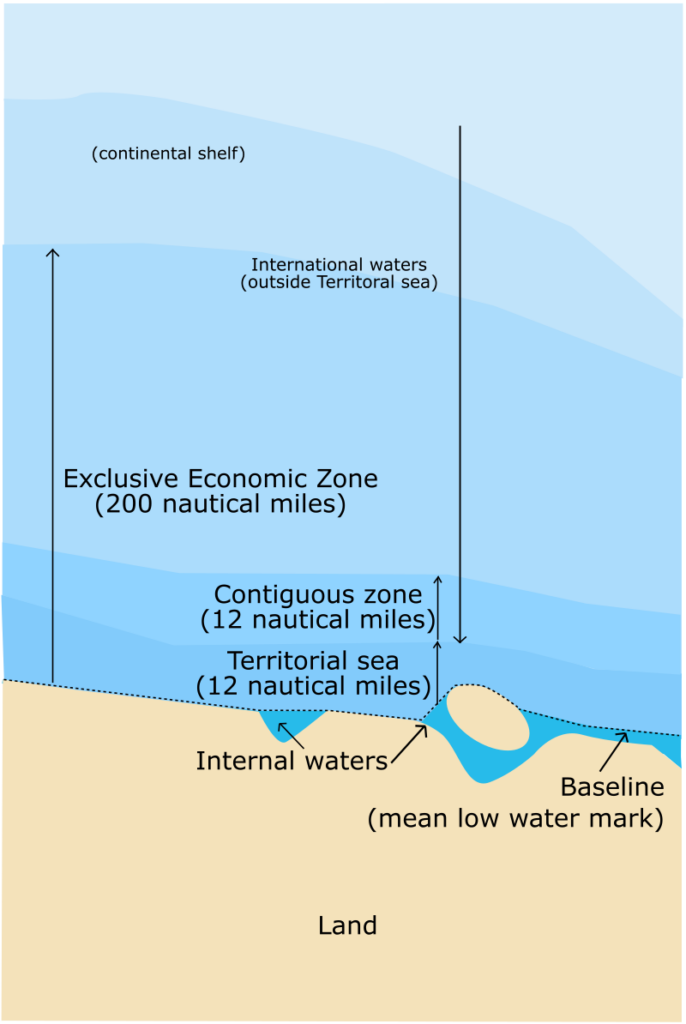

The following image shows the EEZ location from baseline water mark.

Seabed Mining Project Area

- Proposed Mining Area: Trans-Tasman Resources (TTR) plans to mine approximately 150-200 square kilometers of the seabed over a 20-year period. (Source: Wikipedia)

- Exploration Permit Area: TTR holds an exploration permit covering 6,319 square kilometers within the South Taranaki Bight. (Source: Environmental Protection Authority)

Based on the current project design and production schedule, TTR proposes to mine approximately 150 to 200 square kilometres (km²) of seabed area over the 20-year mine life.

Breakdown:

- The seabed crawler operates in 300m x 300m (0.09 km²) blocks.

- Each block takes about 10 days to complete, and ~36 blocks are mined per year (based on a 365-day schedule with 72% utilisation).

- That equates to ~3.24 km² mined per year.

- Over 20 years:

3.24 km²/year × 20 years = ~65 km²(minimum operational footprint).

However, allowing for:

- Overlaps in block transitions

- Anchor/mooring repositioning zones

- Additional lateral flexibility

- Expansion into Kupe South and Tasman South later in the mine schedule

The realistic upper range is 150–200 km² across both:

- MMP55581 (Mining Permit – EEZ)

- MEP54068 (Exploration Permit – Territorial Waters)

This mining footprint is small compared to the overall permitted resource area, which spans hundreds of square kilometres, but only a fraction is mined at any one time.

Comparative Scale

- The South Taranaki Bight spans over 30,000 km².

- TTR’s proposed mining area is just 65 km² — less than 0.22% of the total bight.

- That’s equivalent to mining one quarter of a postage stamp on a football field.

Summary - TTR is not proposing to mine the entire South Taranaki Bight—just the 65.76 km² in MMP55581 over 20 years.

- The 509 km² total across both permits defines their maximum potential operational envelope.

- The actual mined area over the life of the project is less than 70 km², but the permits secure access to ~509 km², from which blocks can be selected, mined, and rehabilitated sequentially.

Quick fact:

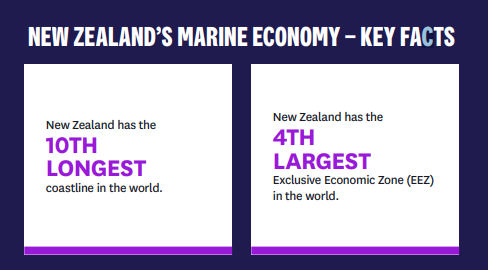

Source: Westpac Blue Economy Research Paper Feb-2025

Geology & Rock Formation

The STB seabed consists of a mixture of:

- Sandy sediments: Deposited by rivers draining into the bight, including the Whanganui, Rangitīkei, and Pātea Rivers.

- Volcanic material: From the Taranaki volcanic system, particularly Mount Taranaki, which has contributed andesitic (iron-rich) sediments to the coastal and offshore environment.

- Sedimentary rock formations: The region is underlain by Cenozoic sedimentary rocks (mainly mudstone, sandstone, and limestone) that form part of the broader Taranaki Basin, which is also a major petroleum exploration area.

How Iron-Rich Black Sands Settled There

The iron-rich black sands in the South Taranaki Bight originate primarily from eroded volcanic material from Mount Taranaki and other volcanic activity along the North Island’s west coast. The process of their deposition occurred through:

Erosion and Transport:

- The iron-rich sands are primarily composed of minerals such as ilmenite, titanomagnetite, and magnetite. These minerals are derived from the erosion of andesitic rocks from Mount Taranaki. Over time, these eroded materials are carried by streams into the ocean, contributing to the iron sand deposits in the South Taranaki Bight. Source: Mindat.org

Wave and Current Action:

- The coastal bed of the South Taranaki Bight is rich with ironsand, formed by the erosion of volcanic rock and concentrated in the bay by sea currents, wind, and tidal forces. Source: Mining Technology

Coastal and Offshore Accumulation:

- The South Taranaki Bight contains significant deposits of iron sands, which have been proposed for seabed mining by companies such as Trans-Tasman Resources. Source: EJ Atlas

Mining Process

The proposed mining operation involves:

- Seabed Extraction – A specially designed crawler would extract approximately 49.5mt (million tonnes) of iron-rich sand from the seabed each year at depths of 20–40 meters.

- Crawler Suction – The sand is sucked up from the seabed to a depth of approximately 11m using a specially designed crawler that manoeuvres along the mining site at very low speeds. There is no dredging of sand.

- Processing on a Floating Vessel – The extracted sand is transferred to a floating processing vessel where separation of iron ore from sand occurs using gravity and magnetic separation techniques. All processing is on board vessels using magnetic separation and desalinated water.

- 90% of extracted sand is returned to the seabed within hours.

- Tailings are deposited 4m above the seabed using a controlled diffuser pipe – reducing plume dispersionTaranaki

- The residual material is dewatered and returned via a controlled fall pipe system at low velocity.

- A diffuser nozzle places the material just ~4 metres above the seabed, minimising plume formation.

- The returned sand is deposited in the same general location it came from – trailing directly behind the mining path.

- This creates a backfill that closely replicates the original seabed topography.

- Export to International Markets – The processed iron ore concentrate would be shipped overseas, primarily to steel manufacturers.

Vanadium Pentoxide (V₂O₅) and Titanium Dioxide (TiO₂) in Trans-Tasman Resources’ Iron Sand Mining Project.

Trans-Tasman Resources’ (TTR) seabed mining project in the South Taranaki Bight primarily targets titanomagnetite iron sands, but these deposits also contain valuable by-products such as vanadium pentoxide (V₂O₅) and titanium dioxide (TiO₂). These minerals have significant industrial and economic value.

Once the iron sands have been exported to Asian markets, credits for vanadium pentoxide (V₂O₅) and titanium dioxide (TiO₂) content will be available once the titanomagnetite iron sands have been processed. These credits are likely to add significant export earnings to the New Zealand economy over many decades as the minerals are sold to international markets.

“Processing iron sands onshore in New Zealand is not feasible due to the lack of necessary infrastructure and expertise for extraction.”

Key minerals identified in New Zealand’s Seabed Deposits

| Mineral | Use & Global Demand | Relevance to NZ Seabed Mining |

| Iron Sands (Iron Ore & Titanium Oxides) | Essential for steelmaking, construction, and infrastructure | NZ’s seabed contains high-grade iron sands, a valuable export commodity. |

| Titanium | Used in aerospace, medical implants, pigments, and coatings | Extracted from iron sands, NZ’s deposits have significant titanomagnetite content. |

| Vanadium | Key for energy storage (VRFBs), steel alloys, and defence | Found in NZ’s iron sands, providing potential for battery production. |

| Rare Earth Elements (REEs) | Used in EVs, wind turbines, semiconductors, and military applications | NZ seabed deposits may contain REEs, but further exploration is needed. |

New Zealand Critical Minerals Strategy

In January 2025, the New Zealand Government unveiled “A Minerals Strategy for New Zealand to 2040,” outlining a strategic vision for the country’s minerals sector. The strategy emphasises three key outcomes: productivity, value, and resilience, all guided by principles honoring Te Tiriti o Waitangi and responsible practices. A significant goal set forth is to double mineral exports to NZ$3 billion by 2035.

Complementing the strategy, the government released a Critical Minerals List identifying 37 minerals essential to New Zealand’s economy and technological needs, including those vital for clean energy and international trade. Notably, gold and metallurgical coal were added to the list, recognising their importance to the country’s minerals sector.

Source: Critical Minerals List

These initiatives aim to position New Zealand as a trusted and reliable partner in the global critical minerals market, particularly in supporting supply chains necessary for clean energy technologies.

Source: Hon Shane Jones – Press Release

For a comprehensive understanding, you can access the full Minerals Strategy document here:

Source: NZ Government – Minerals Strategy to 2040

Where do these minerals rank globally in criticality?

Vanadium and titanium are both recognised as critical minerals due to their essential roles in various industries and potential supply chain vulnerabilities. According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) in their 2024 report, these minerals are categorised based on their criticality for the global energy transition:

- Most Critical: Materials such as lithium, cobalt, and rare earth elements fall into this category.

- Moderately Critical: This group includes vanadium and titanium, indicating a moderate level of criticality.

- Least Critical: Materials like molybdenum and magnesium are considered least critical.

This classification reflects the importance of vanadium and titanium in the energy sector and other applications, balanced against factors like supply risk and availability. Source: irena.org

On the 23 January 2025, The Rt Hon Christopher Luxon, PM, in his state-of-the-nation speech stated;

Fast Track will supercharge economic growth, enabling major investments and growth in energy, transport, aquaculture, and a range of other sectors – but we can go further. This year we will crack on and make big changes. Fourth, mining needs to play a much bigger role in the New Zealand economy.It’s easy in politics to say you want a sovereign wealth fund like Norway, or much higher incomes like Australia – but it’s much harder to say you want the oil and mining that pays for it.

In regions like Taranaki and the West Coast there are big economic opportunities – higher incomes, support for local business and families, and more investment in local infrastructure.

The minerals sector will also be critical for our climate transition – EVs, solar panels, and data centres aren’t made out of thin air.I want to see mining employ more Kiwis and power more growth in the economy and I’m adamant we must take further steps to make that a reality.

Economics

Bankable Feasibility Study (BFS)

If TTR secures the necessary consents, expected in late 2025, they will then need to undertake a Bankable Feasibility Study (BFS). A BFS is a comprehensive assessment that confirms the technical, economic, and environmental viability of a project, providing the level of confidence required for investors and financiers to commit capital.

A key component of the BFS is critical metallurgical testing, which is essential for validating the processing and recovery of valuable materials. This testing provides data on:

- Ore Characterisation – Understanding the composition, grade, and variability of the resource.

- Processing Efficiency – Determining the optimal methods for extraction, separation, and refinement.

- Recovery Rates – Assessing how effectively valuable minerals can be extracted, which directly impacts financial modelling.

- Product Quality – Ensuring that the final product meets market and customer specifications.

- Scaling and Optimisation – Evaluating how laboratory-scale results translate to full-scale operations.

By integrating metallurgical testing with engineering, economic modelling, market analysis, and risk assessment, the BFS will provide a robust foundation for securing investment and advancing the project to development.

Economic & Strategic Importance to New Zealand

Export Potential: Iron sands and titanium-rich minerals can position New Zealand as a key supplier for global steel and aerospace industries.

Renewable Energy Supply Chain: Vanadium and possible Rare Earth Elements (REEs) in seabed deposits could support energy storage and green technology initiatives.

Local Job Creation: The mining sector could drive employment and economic growth in regional New Zealand and in the case of seabed mining, Taranaki.

Strategic Mineral Independence: As the world shifts away from China-dominated mineral supply chains, New Zealand could benefit from new partnerships in mineral exports.

Project Economics – New Zealand and the Taranaki/Whanganui districts

The 2025 NZIER economic impact assessment for TTR’s Taranaki VTM Iron Sands Project outlines substantial national and regional benefits. Here’s a breakdown of the published economics as of February 2025:

🇳🇿 Economic Contribution to New Zealand

| Metric | Annual Impact |

|---|---|

| GDP Contribution | $246 million |

| Jobs Created | 1,320 jobs |

| Iron Ore Export Revenue | $763 million |

| Royalties to the Crown | $36–$53 million |

| Corporate Tax | $91–$134 million |

- TTR’s operation is expected to be one of the top 15 export sectors by value.

- NZD $1 billion capital investment in offshore mining and shipboard processing infrastructure.

🌏 Regional Impact (Taranaki + Whanganui)

| Metric | Annual Impact |

|---|---|

| GDP Contribution | $205 million |

| Jobs Created | 1,093 jobs |

- Over 303 direct FTE jobs created by TTR.

- $217 million in annual direct operating expenditure will be injected into the Taranaki regional economy.

🏘 Local Impact (South Taranaki + Whanganui Districts)

| Metric | Annual Impact |

|---|---|

| GDP Contribution | $40 million |

| Jobs Created | 249 jobs |

| Local Spending | $47 million |

📦 Revenue & Resource Production

- 4.9 million tonnes per annum (Mtpa) of iron ore concentrate exported.

- Revenue based only on iron ore concentrate sales only – vanadium (V₂O₅) and titanium dioxide (TiO₂) sales were not included in these estimates.

- TTR notes these by product credits could double project revenue, increasing royalty and tax returns to the Crown.

💰 Sensitivity Notes

- Royalties are more sensitive to iron ore prices than to fuel costs or NZD/USD exchange rates.

- Vanadium and titanium recovery potential:

- ~19,000 tonnes/year V₂O₅

- ~327,000 tonnes/year TiO₂

Jobs

What’s in it for the Taranaki region?

The proposed project is estimated to provide the Taranaki region with:

Employment:

- A corporate head office based in New Plymouth with up to 50 professional roles

- Up to 300 FTE* roles relating to the integrated mining ship and support services

- Up to 170 FTE induced roles (businesses that employ additional staff because of the new roles created and new disposable income spent in the region

The average salary is estimated at $125,000 per FTE ensuring that the project increases the regional salary per capita levels back to pre-2016 oil & gas period.

* The 300 FTE roles include helicopter pilots, vessel captains, vessel crew, chefs, housekeepers, medical, H&S, security, training etc. These are all new roles working rotating shifts on the vessels.

GDP

The annual spend from the project operations within the Taranaki region is estimated to be approximately $250m per year. This includes wages and salaries of employees, and the operational expenditure associated with running the project day-to-day. The project is expected to provide a massive boost to the Taranaki regional economy over many decades. Source: Martin Jenkins Independent Report 2015

Referencing the above economic information and source. In February 2025, New Zealand Institute of Economic Research (NZIER) provided a independent report of the Taranaki VTM Project and you can view a copy of this here.

Fiction vs Fact

To correct misinformation and false claims

| Fiction | Fact |

| The market cap of Manuka Resources suggests that TTR, if granted consents, is not financially viable and will be unable to fund the project. | The current market cap is irrelevent. If TTR secures the necessary consents, they will proceed with a Bankable Feasibility Study (BFS). A BFS is a comprehensive technical and financial assessment that evaluates the viability of a project to a level of detail sufficient for securing investment and project financing. This study is essential because it provides the confidence needed by international investors, lenders, and stakeholders, demonstrating that the project is economically, technically, and environmentally feasible. |

| Opposition parties, namely The Greens and Te Pati Maori, have stated that should there be a change of Government at the next election they will seek to have the seabed mining consents cancelled. | When a government changes, opposition parties may seek to alter or withdraw project consents. However, sovereign rights and international investment protections prevent arbitrary revocations. Legally granted consents remain valid regardless of political shifts. Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) and Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) protect foreign investors from unfair government interference. |

| Trans-Tasman Resources Limited is an Australian company. | Trans-Tasman Resources Limited is a New Zealand incorporated company and a subsidiary of ASX listed Manuka Resources Limited ASX:MKR |

| The profits generated by the company will all go offshore | Approximately 20% of the shareholders reside in New Zealand and many within the Taranaki region. Profits provide dividends and these dividends will go to the local investors to be spent in our communities. Profits are taxed in New Zealand and royalties are generated. This revenue goes to the New Zealand Government to fund health, education, jobs etc. |

| Jobs will go to overseas interests and operate on a fly in – fly out basis. | Over 1600 jobs nationwide and 470 direct and induced in the Taranaki region will be generated by the seabed mining project. With a average salary of $125,000 this will result in renewed high paying jobs and new consumer spending in the region. |

| The project was approved without proper environmental assessment, ignoring potential harm. | The seabed mining project underwent extensive environmental impact assessments and in 2017 was approved by regulatory authorities based on scientific evidence and its marine consents were granted. |

| “TTR has faced legal defeats at every level in its attempts to secure consents, with strong opposition from Ngāti Ruanui Iwi, Kiwis Against Seabed Mining (KASM), Greenpeace, and others.” | TTR was granted marine consents in 2017. However, following appeals by opponents, it was determined that the consents, as considered and approved by the EPA, were inconsistent with the law at the time. Around 2020, Attorney General Hon. David Parker intervened, leading to amendments in the legislation. The Supreme Court ultimately quashed TTR’s appeal but left the door open for the company to reapply for its consents with the EPA based on the redefined law. |

| Seabed mining will completely destroy marine ecosystems and lead to widespread biodiversity loss. | The project will use advanced technology to minimise environmental disturbance, including measures to reduce sediment plumes and the impact on marine life. |

| The seabed mining operation will release toxic substances into the ocean, harming fisheries and human health. | The iron sands extracted from the seabed contain minimal toxic elements, and independent studies show no significant long-term environmental risks. |

| Seabed mining only benefits foreign corporations while leaving local communities with environmental damage. | The project will create jobs and economic benefits for New Zealand, contributing to local and national growth. The environmental impact is negligible. |

| The company has not properly consulted with local communities and Māori groups, disregarding their concerns. | The project owners have engaged in extensive consultation with stakeholders, including iwi groups, environmental organisations, and regulatory bodies. Source: Evidence |

| There has been insufficient stakeholder engagement with the community and in particular with Iwi groups in South Taranaki. | The company has undertaken extensive engagement with the community and in particular South Taranaki Iwi groups. Source: Evidence |

| TTR has not been transparent with the community or made available all the key evidence to support its 2016 application. | Full expert evidence of the TTR application for consent made to the EPA in 2016 and from which consents were granted in 2017 Source: Evidence |

| TTR has bypassed normal environmental scrutiny by using the Fast Track process. | Should TTR have its consents approved, they will have significant and robust environmental conditions attached which the Fast Track expert panel will assess as part of the approvals process. |

| Source: Evidence | There is insufficient information available that provides evidence for or opposition to, seabed mining |

Sediment Plume

Opposition to seabed mining includes sediment plume behaviour. That is, the iron sands that are pumped back onto the seabed once the extraction process has been completed, and the effects this creates. In 2017, a worst-case scenario was presented to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for consideration.

Update: TTR has provided the Fast Track panel with updated information relating to sediment plume. The new plume modelling submitted for the Fast Track Panel’s consideration by Trans-Tasman Resources (TTR) includes several key updates and refinements aimed at addressing previous uncertainties and concerns regarding the sediment plume generated during iron sand extraction. Here are the main aspects of the new plume modelling:

- Refined Modelling Techniques : TTR has engaged international experts, including HR Wallingford Ltd (HRW), to conduct peer reviews and further testing of the original sediment plume models developed by NIWA. This has led to more accurate modelling of the plume’s behavior in the marine environment.

- Incorporation of Flocculation : The new modelling takes into account flocculation, a process where fine sediment particles aggregate into larger, faster-sinking clumps. This was previously neglected in earlier models, and its inclusion allows for a better understanding of how sediment behaves after being discharged.

- Updated Sediment Settling Rates : The modelling has refined the predictions regarding sediment settling rates. It indicates that fine suspended sediment is expected to settle to the bottom and be trapped in the matrix of discharged sand to a greater extent than previously assumed.

- Sediment Re-suspension Analysis : The new modelling has also improved the understanding of sediment re-suspension. HRW’s testing found that the shear stress required to re-suspend freshly deposited material is higher than originally estimated, which affects predictions about the persistence and dispersion of the sediment plume.

- Comprehensive Assessments : The updated modelling includes detailed assessments of the plume’s source terms, characteristics, and dispersion patterns. This comprehensive approach aims to provide greater certainty regarding the potential environmental impacts of the iron sand recovery operations.

- Addressing DMC Concerns : The new modelling specifically addresses concerns raised by the Decision-Making Committee (DMC) in the previous marine consent application, including uncertainties about the scale of effects, impacts on primary production, and the lack of compliance levels.

- Peer Review and Validation : The modelling has undergone extensive peer review and validation processes to ensure its accuracy and reliability. This includes input from various specialists and experts in marine science.

These updates are part of TTR’s efforts to enhance the understanding of the environmental impacts associated with their proposed activities and to provide the Fast Track Panel with robust scientific data for their decision-making process

Conclusions

The conclusions from the modelling of the worst-case scenario are that the plume of mining-derived sediment contributes significantly to the total suspended sediment concentration within a few kilometres of the mining operation but is insignificant relative to the background suspended sediment concentration near the coast. This plume behaviour is similar to that previously presented to the Hearing in the evidence of Dr Dearnaley with some (mostly small) differences in suspended sediment concentration. The main difference is that the area of higher sediment plume concentrations increases and extends further alongshore. The new worst-case scenario has the greatest effect on extreme statistics (99th percentiles), with the difference being small to indiscernible in the median values. Deposition from the plume increases slightly in the worst-case modelling scenario compared to the previous simulation. The deposition footprint, as with the previous simulations, can be distinguished from the background only within a few kilometres of the mining operation.

References Hadfield, M.G and MacDonald, H.S. (2015) Sediment Plume Modelling, October 2015. Joint Statement of Experts in the Field of Sediment Plume Modelling – Setting Worst Case Parameters. Before the Environmental Protection Authority, 23rd February 2017. MacDonald, H.S. and Hadfield M. G (2017) South Taranaki Bight Sediment Plume Modelling: Worst case Scenario, March 2017.

You can view the 2015 Niwa Sediment Report here IMPORTANT: The latest plume modelling from 2025 will be released once the full Fast Track Application goes before the Expert Panel which is expected in late June 2025.

Update July 2025: Despite what opposition groups claim – the substantive application submitted to the Fast Track panel for consideration has updated modelling and data, inluding plume modelling.

Is there Geopolitical Importance for the Seabed Mining Project

Yes, geopolitical strategy is highly relevant in this case. The mining of vanadium and titanium in New Zealand could have strategic implications, particularly in relation to New Zealand’s relationships with the United States, China, and its role in the broader Indo-Pacific security framework.

1. The Role of Vanadium and Titanium in Global Supply Chains

Vanadium is crucial for steel strengthening, aerospace, and emerging battery technologies (such as Vanadium Redox Flow Batteries, which are seen as key for large-scale energy storage).

Titanium is essential for aerospace, military, and industrial applications, particularly in defence manufacturing (e.g., fighter jets, submarines, and missiles).

The fact that China and Russia dominate production, while the USA lacks significant domestic sources, makes alternative supplies highly valuable.

2. Potential for a U.S.-New Zealand Strategic Minerals Agreement

Given the USA’s increasing focus on securing critical mineral supply chains, New Zealand could position itself as a trusted Western supplier of vanadium and titanium. The Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), which the U.S. is promoting, emphasises securing reliable mineral sources outside of China.

New Zealand could negotiate marketing agreements with the United States or its allies (such as Australia and Japan)to ensure these minerals are directed to friendly markets rather than China.

3. Defence and Security Implications for New Zealand

The U.S. recognises resource security as a key aspect of defence and strategic planning.

If New Zealand commits to supplying vanadium and titanium to the U.S. and allies, it strengthens its defence relationship.

In return, the U.S. could:

Increase military cooperation with NZ, including intelligence sharing and defence technology transfers.

Provide diplomatic support for New Zealand’s strategic initiatives.

Enhance its role in South Pacific security, offering more direct engagement in maritime surveillance, cybersecurity, and regional defence.

4. How This Aligns with the Fast-Track Process

The New Zealand government’s fast-tracking of the project aligns with broader Western efforts to counter China’s dominance in critical minerals. Approval of the project could position New Zealand as a strategic resource partner, reinforcing its economic and security ties with the U.S. and its allies.

Conclusion

If New Zealand does not move forward with the project, it risks allowing China or Russia to continue their near monopoly, which could limit Western access to these minerals.

If New Zealand can supply critical minerals to Western allies, it:

Enhances its economic leverage by becoming a key supplier of vanadium and titanium.

Strengthens its defence relationship with the U.S., ensuring continued security cooperation.

Positions itself as a reliable alternative to China and Russia in the mineral supply chain.

Given these factors, New Zealand has a strong incentive to approve the project and leverage it for strategic advantages in international defence and trade partnerships.

Wind v Mining

The South Taranaki Bight Debate

Since 2007, Trans-Tasman Resources (TTR) has been exploring the South Taranaki Bight, undertaking extensive exploration research. To date, the company has invested over $85 million, funded by various investors and capital raises through its parent company, Manuka Resources (MKR:ASX).

TTR’s Permits

TTR holds two key permits for its operations in the South Taranaki Bight:

Minerals Mining Permit

In May 2014, TTR was granted a mining permit (MMP55581) under the Crown Minerals Act 1991, allowing the extraction of up to 50 million tonnes of iron sand annually over 20 years from a 66 km² area. Environmental Protection Authority

In July 2024, this permit area was expanded to 243 km². Newsroom

- Minerals Mining Permit 55581 (MP55581): This permit allows TTR to extract up to 5 million tonnes of seabed material annually, subject to Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) approvals.

- Mineral Exploration Permit 54068 (EP54068): This permit, granted in 2024, covers exploration activities in the same region. The permit encompasses approximately 635 square kilometres and is crucial to TTR’s Taranaki VTM (vanadium titanomagnetite) iron sands project, which aims to harvest iron sands containing iron ore and critical minerals like vanadium and titanium.

Offshore Wind Farm Development

In recent years, proponents of offshore wind farms have identified the South Taranaki Bight as a viable location for large-scale renewable energy infrastructure. The Taranaki Offshore Partnership, a joint venture between Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners and the New Zealand Super Fund, is spearheading the development of an offshore wind farm capable of generating up to 1 gigawatt (GW) of electricity, contributing significantly to New Zealand’s renewable energy objectives. Source: TOP Website

Compatibility: Wind vs. Mining

A key question has emerged: Can wind farms and seabed mining operations coexist in the same location? The short answer is no. Wind turbines cannot be constructed within an active seabed mining zone, and conversely, seabed mining cannot operate in and around a wind farm.

Who Has Priority?

TTR already holds confirmed permits for seabed mining, pending approved marine consents. If these consents are granted by June 2025, mining operations could commence within two years, following infrastructure development.

Once consents are approved, it will not be possible for wind farm developers to proceed with construction in the same location.

Hon. Shane Jones’ Perspective

In a recent interview with The Australian, New Zealand’s Resources Minister, Hon. Shane Jones, addressed the ongoing debate between offshore wind farm development and seabed mining. He emphasised the vastness of the ocean, suggesting that there is ample space for both industries to coexist. Jones urged wind farm operators to “move over,” indicating that they should make room for mining activities, given the expansive maritime area available. He criticised opposition to seabed mining, describing it as rooted in “shrill” environmental alarmism and “luxury beliefs.” Jones emphasised the importance of balancing environmental concerns with economic development, suggesting that economic growth should not be hindered by what he perceives as overly cautious environmentalism.

Source: The Australian

Coexistence and Future Prospects

While seabed mining and offshore wind farms can coexist in different locations, regulatory and operational challenges remain. Importantly, if TTR’s marine consents are not approved, this does not mean the company automatically forfeits its permits. Instead, TTR may choose to:

- Continue research and development for seabed mining.

- Reapply for consent under modified conditions.

- Explore alternative uses for the permitted area, including potential wind energy projects.

Conclusion

The best outcome for New Zealand and the Taranaki region would be a structured approach where both industries contribute to economic development. However, regulatory certainty and clear decision-making are essential to determine the future landscape of resource utilisation in the South Taranaki Bight.

If marine spatial planning (MSP) were adopted as part of the Offshore Wind Energy Bill currently before Parliament’s select committee, it would likley have significant implications for both offshore wind energy and seabed mining in New Zealand’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) and territorial waters. However, marine spatial planning would provide certainty for all developers by designating areas for offshore wind, seabed mining, and other activities thus ensuring more clarity, reducing conflicts, and avoiding unnecessary delays.

Update July 2025: In March, 2025, the following statement was reported. “A giant wind farm could co-exist with Trans-Tasman Resources’ proposed seabed mining scheme off the coast of Taranaki, despite earlier doubts, says Giacomo Caleffi, director of wind developer Taranaki Offshore Partnership.”

The message from offshore wind developers about seabed mining was once ‘one or the other, you can’t have both’.

Now that has morphed into the suggestion both could be possible.

Source: https://www.thepost.co.nz/business/360625653/why-one-offshore-wind-developer-hasnt-given-nz-yet

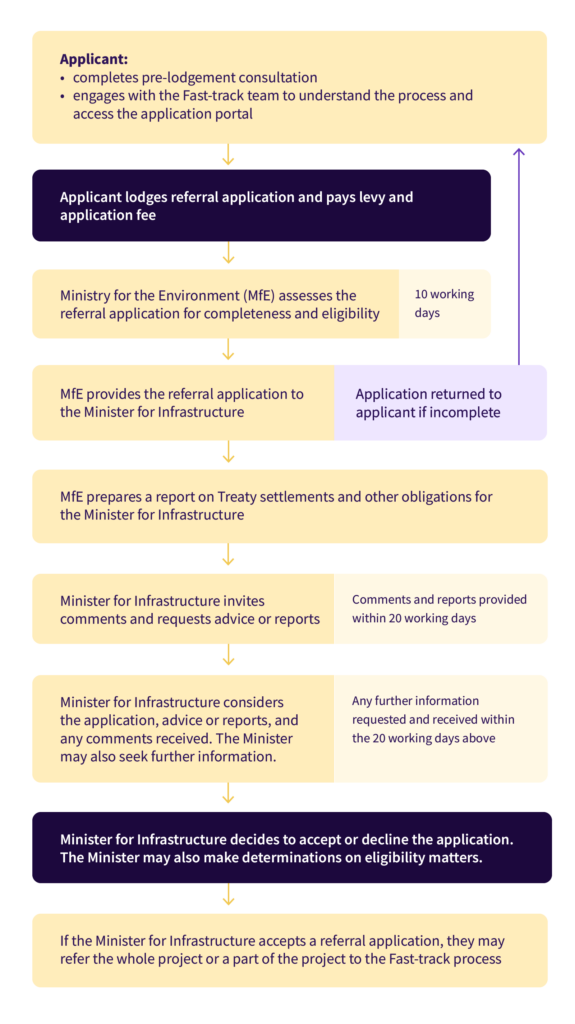

Fast-Track Process

Fast-Track Process

In December 2024 the New Zealand Government passed into law the new Fast-Track legislation designed to speed up the consenting process for major projects or regional and national significance. The seabed mining project has been accepted into the Fast-Track programme and the status of any application can be found here Source: Fast Track – Taranaki VTM Project

Fast Track Process for Applications

The Fast Track Process ensures that applications are assessed efficiently while maintaining robust environmental and regulatory scrutiny. Below is an overview of the key steps, expected timeframes, and the appeals process. Note that this information may be subject to change.

Key Steps and Timeframes

- Pre-Application Consultation (Recommended: 3–6 months before submission)

- Engagement with regulatory authorities, iwi/hapū, stakeholders, and affected parties

- Preliminary environmental and technical assessments to identify potential impacts

- Application Submission

- Lodgement of a complete application with all supporting documentation

- Public notification period (20 working days) for submissions from interested parties

- Review and Assessment (Expected: 6–9 months from lodgement)

- Regulatory agency review in accordance with the Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf (Environmental Effects) Act 2012 (EEZ Act)

- Independent expert evaluations and request for further information if required

- Public hearing (if required) held within 40 working days of the submission deadline

- Decision Issued (Within 20 working days of final hearing or assessment completion)

- The Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) issues a decision based on environmental, economic, and technical considerations

- Conditions imposed where necessary to mitigate potential impacts

Appeals Process

The court may confirm, modify, or overturn the decision if a legal error is found.

Appeals are strictly limited to points of law under Section 105 of the EEZ Act 2012.

This means an appeal cannot re-examine the facts or introduce new evidence—only legal errors in the decision-making process can be challenged.

Appeals must be lodged with the High Court within 15 working days of the decision being issued.

Substantive applications – please refer to Source: Fast Track – Substantive Application

The following diagram shows the typical key steps for applications and time frames

Sustainable Seabed Mining: TTR and EPA Conditions

Final thoughts….

Trans-Tasman Resources (TTR) has proposed a seabed mining operation off the coast of New Zealand, targeting iron sand extraction while adhering to strict environmental sustainability measures. The New Zealand Environmental Protection Authority (EPA) originally granted marine consent in 2017, imposing 109 conditions to ensure the operation minimises environmental harm. These conditions are designed to protect marine ecosystems, manage sediment dispersion, and uphold water quality standards.

Key Environmental Safeguards in TTR’s Marine Consent Conditions

1. Sediment Plume Management

- TTR must implement measures to control and monitor sediment dispersion, preventing excessive impact on marine ecosystems.

- The project must use real-time monitoring systems to track sediment movement and ensure compliance with EPA-imposed thresholds.

- If sediment levels exceed prescribed limits, operations must be adjusted accordingly.

(Source: EPA Marine Consent Decision, 2017; TTR Environmental Impact Assessment)

2. Protection of Marine Life and Benthic Environment

- Mining activities are restricted to low-productivity seabed areas to minimise ecological disruption.

- TTR must conduct comprehensive pre-mining baseline assessments to understand the existing ecosystem.

- The establishment of exclusion zones ensures protection of sensitive species and habitats.

(Source: EPA Marine Consent Decision, 2017; TTR Environmental Impact Assessment; Independent Technical Reports submitted during the consent process)

3. Water Quality and Heavy Metal Containment

- The EPA conditions require that discharged water meets strict quality standards to prevent contamination.

- TTR’s system is designed as a closed-loop operation, meaning that 90% of the mined material (mainly iron sand) is returned to the seabed, reducing overall disturbance.

- Heavy metal leaching is monitored continuously, with contingency plans in place if toxic levels are detected.

(Source: EPA Marine Consent Decision, 2017; TTR Environmental Impact Assessment; High Court Decision on TTR v. EPA)

4. Independent Monitoring and Compliance

- TTR must establish an independent Technical Advisory Group (TAG) to oversee environmental performance and compliance with consent conditions.

- Continuous monitoring is required, with data reported to regulatory authorities to ensure transparency.

- If environmental effects exceed predicted limits, mitigation measures must be implemented immediately.

- Environmental Monitoring – A 27-Year Commitment to Accountability and Safety

The Taranaki VTM Project has one of the most extensive environmental monitoring regimes ever applied to a marine project in New Zealand. This is not optional, nor is it self-policed. It is legally binding, independently verified, and continuously enforced. - Timeline of Monitoring and Oversight (27 Years Total):

2 years (pre-mining)

Comprehensive data collection on benthic life, sediment, water quality, whales, fish, and habitats. Establishes clear environmental reference points.

Operational Monitoring

20 years

Continuous real-time monitoring during mining. Independent scientists measure sediment plumes, biodiversity recovery, noise, and water quality. Adaptive management plans kick in if thresholds are exceeded.

Post-Production Monitoring

5 years

Verification that seabed conditions return to expected baselines. Any unforeseen changes trigger responsive action under the EPA-enforced management plans.

What’s Being Monitored:

Seabed recovery and benthic ecology

Sediment plume extent and dispersal

Marine mammals, particularly blue whales and Māui dolphins

Water quality and sediment chemistry

Noise levels and underwater acoustics

Cumulative ecosystem effects

Enforcement and Independent Oversight

The entire regime is overseen by the Environmental Protection Authority (EPA).

An Independent Technical Advisory Group (TAG) includes scientists, local iwi, regional councils, and commercial stakeholders (e.g. fisheries).

Data and reports are made public.

If anything exceeds consented limits, mining must pause immediately until adaptive responses are applied and conditions stabilise.

(Source: EPA Marine Consent Decision, 2017; Court of Appeal Decision on TTR v. EPA)

5. Marine Mammal Protection

- A Marine Mammal Impact Management Plan must be in place, ensuring adherence to protocols for detecting and avoiding marine mammals.

- If certain species (e.g., whales or dolphins) are detected within a specific radius, mining activity must pause to avoid disturbance.

- Underwater noise levels must remain within EPA-set thresholds to prevent adverse effects on marine life.

(Source: EPA Marine Consent Decision, 2017; Independent Expert Submissions on Marine Mammals; TTR Environmental Impact Assessment)

Economic and Environmental Balance

Compared to land-based iron sand mining, TTR’s offshore operation provides several advantages:

- Avoids deforestation and land degradation associated with terrestrial mining.

- Eliminates freshwater contamination from mining tailings.

- Reduces carbon emissions, as offshore transport is more efficient than trucking and rail transport from land-based mines.

- Generates economic benefits, including job creation, regional development, and reduced reliance on imported iron ore.

(Source: NZ Government Fast-Track Policy 2024; NZ First Policy Statements; Economic Reports on Seabed Mining)

TTR and the Fast-Track Process

- The EPA originally approved TTR’s consent in 2017, but legal challenges overturned the decision based on procedural grounds, rather than environmental impacts.

- The current fast-track consenting process provides an opportunity to re-evaluate the project, ensuring compliance with New Zealand’s environmental and economic objectives.

- The New Zealand government, particularly NZ First and Minister Shane Jones, supports the project as part of a broader strategy for economic growth and resource development.

(Source: NZ Government Fast-Track Consenting Process, 2024; Court Decisions on TTR v. EPA)

Conclusion

TTR’s seabed mining project has the potential to be both environmentally sustainable and economically beneficial, provided it adheres to the strict EPA conditions. By ensuring rigorous environmental monitoring, protection of marine life, and responsible sediment management, the project can proceed in a manner that balances economic development with marine ecosystem conservation.

Strict adherence to the consent conditions will be critical in gaining public and regulatory confidence, ensuring that seabed mining in New Zealand is conducted in a responsible and sustainable manner.

(Sources: EPA Marine Consent Decision 2017; High Court and Court of Appeal Decisions on TTR v. EPA; TTR Environmental Impact Assessments; Independent Scientific Reports; NZ Government Fast-Track Consenting Process 2024).

Take the poll

Ready to take the poll?

Seabed mining in the Taranaki region can provide economic and strategic benefits over many decades where critical mineral extraction can be undertaken. This economic outcome also needs to be weighed against the environmental effects to arrive at a balanced view. If the project can provide significant prosperity to the New Zealand and Taranaki regional economies through new high paying jobs, taxes and royalties, and where the project can be undertaken with minimal environmental harm with robust consent conditions, where do you sit?

Disclaimer

The information and opinions expressed on this website are solely those of the website owner and do not reflect the views, positions, or policies of Manuka Resources Limited (ASX:MKR) or its 100% owned entity, Trans-Tasman Resources Limited (TTR).

This website is for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial, legal, or investment advice. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the content, no guarantees are made regarding its completeness, timeliness, or reliability.

Manuka Resources Limited and Trans-Tasman Resources Limited are not responsible for, nor do they endorse, any content, statements, or representations made on this site. Any reliance you place on the information provided is strictly at your own risk.

For official information regarding Manuka Resources Limited or Trans-Tasman Resources Limited, please refer to their official communications and regulatory disclosures.